Select Page

The Alpine Tundra

The Alpine Tundra is a unique biome in that it’s found all over the globe, but only on tops of the tallest mountains. While temperature and rainfall usually determine the other biomes, this one is defined mostly by elevation. This elevation causes extreme conditions, which create a unique tundra environment where only the hardiest plants and animals can survive.

Alpine Tundra

A treeless tundra on the tops of mountains

The Alpine tundra is an interesting biome because it is not found at a certain latitude like most biomes, but instead at high altitudes in the mountains. Located in both the Northern and Southern Hemisphere, this biome is defined by the harsh conditions brought on by high elevation, such as high dry winds, low temperatures, poor soil, and a distinct lack of trees.

Note: The arctic tundra is also defined by harsh weather and lack of trees, however, the thing that most restricts tree growth there is the permafrost in the soil. We treat the arctic tundra biome in its own section.

What defines the alpine tundra biome? What is the climate of the alpine tundra biome? What lives in the alpine tundra? What adaptations do alpine tundra plants and animals have that allow them to survive here? That’s what you’ll learn by spending a few minutes browsing this article and associated media.

THE MERRIAM LIFE ZONES

Merriam mapped the life-zones with elevation. Today, we still use these life-zone classifications.

In the late 1800’s a man by the name of C. Hart Merriam was surveying the land in The United States from the bottom of the Grand Canyon to the top of the mountain peaks. He noticed that distinct plant communities were found as one increased elevation. He noticed at lower elevations there were prairies, then dry steppes, ponderosa pine, montane forests, subalpine forests and finally the alpine tundra.

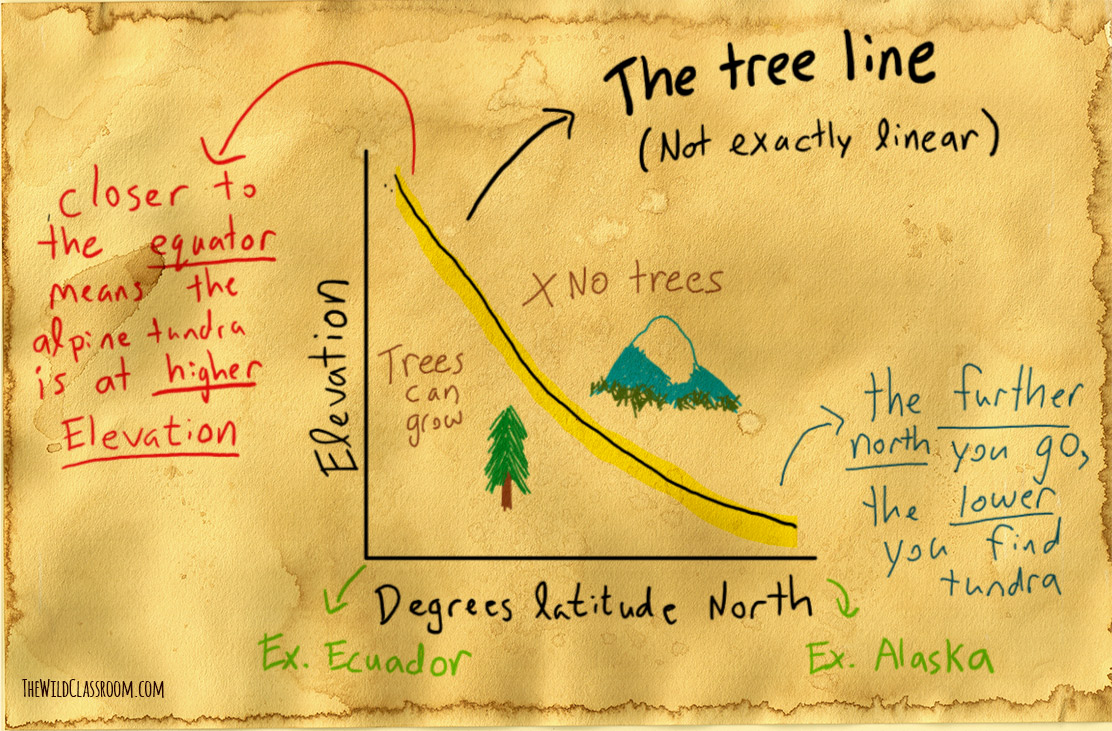

These life-zones will change with elevation, but they are also tied to latitude. How?

Let’s look at the elevation of the alpine tundra from the equator going north, for example. As you go up in elevation, it is similar to you travelling north in latitude, where the higher you go the colder and harsher it gets until you reach the alpine tundra. However, the further north you go, the less you have to travel up the mountain to reach the alpine tundra. That means you reach the alpine tundra at lower elevations the farther north you are.

Note: This graph is a representation from the equator going north, but a similar pattern is shown as you go south of the equator – the treeline also appears at lower elevations the further south you go, but the peak for highest treeline is a bit south of the actual equator. It is also important to know that the treeline is not exactly the same at one latitude all the way around the earth.

Long story short, when you are closer to the equator, you have to go to higher elevations to find alpine tundra, but the further north or south you go, the lower in the mountains you can find alpine tundra.

WHERE IS THE ALPINE TUNDRA FOUND?

The interesting part of this biome is that the “line” that defines the alpine tundra can often be seen by an actual line, known as the treeline: the altitude where trees can no longer grow. As you go up the side of a mountain, the trees become thinner, and at some point stop growing, this line, though normally not very straight, is where you will find alpine tundra. As mentioned before, the treeline is found at lower elevations further north and south, and higher elevations closer to the equator, mostly because of milder climate around the equator. Once you go far enough north (North of 60°), trees no longer grow due to permafrost, and the biome is then considered arctic tundra.

The exact thing that defines the treeline is still being studied, but the main hypothesis is that it is too hard for seeds to disperse and start to grow there, and/or that adult trees can not grow in the high altitude conditions, mainly due to the cold. You can find a detailed scientific report on treelines here.

Some notable regions with a large amount of alpine tundra are: The Himalayas, The Tibetan Plateau in Asia, The Caucasus Mountains, The Rift Mountains in Africa, the American Cordillera in North and South American, The Alps, and the Pyrenees and Scandes Mountains found in Europe.

Essentially, the alpine tundra can be found throughout the whole world, at high elevations above the treeline. To give some examples of the height in which we reach alpine tundra:

In Colorado, USA, the Tundra begins around 3,500 m (11,500 ft) above sea level. Farther north, in Alaska, the Tundra can form at only a few thousand feet elevation (maybe 500-600m)!

On tall Mexican Volcanoes, the tree-line is much higher than anywhere in the United States, occurring around 4000 m (13,000 ft). Right on the equator, and a bit further south, the tree line can even pass this.

The Alpine Tundra Biome Video

WHAT DEFINES THE ALPINE TUNDRA?

The alpine tundra is characterized by low temperatures and low precipitation; harsh cold winds; low-lying vegetation; thin, dry, and poorly developed soils; and rapidly changing weather. These conditions limit tree growth making the alpine tundra a treeless habitat. The growing season is approximately 180 days, but varies a bit depending on latitude.

Within the main alpine tundra habitat, there also exists a variety of microhabitats, influenced by altitude, soil quality, snow accumulation, degree of the slope and aspect (direction that the slope faces – which influences how much light, wind, and rain an area gets).

Essentially, The alpine tundra is not a homogenous zone where plants have equal opportunity to grow. Small changes in elevation in this zone and patches of snow and rock create microhabitats where different species of plant and animal can specialize. For instance, a small depression on the ground might decrease sun and wind intensity causing snow to accumulate. Snowbanks are hard places for plants to grow because areas where snow builds up decrease the already short growing season, as it takes so long to melt. So, small elevation changes that increase light intensity may be just enough for small plants to make a living.

Some of the major microhabitats found in the Alpine tundra are meadows, snow beds, talus fields, and fell-fields, as well as large areas of rock where only some mosses and lichens manage to grow. There is also an area of transition between the treeline and the forest where you will find pockets of trees and larger shrubs. This area is quite small and is normally around 100 meters long, unlike the arctic tundra where the transition zone is much larger.

It is also important to know that the high altitude actually results in low air pressure and lower oxygen which requires specific adaptations. In the highest alpine tundras it is hard to find any mammals at all because of the low oxygen levels. If you have ever hiked in very high altitudes, you will definitely understand why!

Temperature in the alpine tundra

The temperature will vary based on how close to the equator you are, but the alpine tundra is always much colder than the same region at lower altitudes.

It’s really hard to generalize alpine tundra temperatures because they are found all over the world, however, we can give you some general numbers that do not include the extremes: summers range from 3 – 12 °C (37 – 54 °F) with winters around -12 °C (9°F) that are not normally colder than -18 °C (0 °F). Alpine tundra found closer to the equator will experience less strong seasonality, even in these high altitude areas. Whereas further north, winters are longer and the temperature may stay below 0 for 7-8 months of the year, even dipping down to -20°C (68 °F). In the extremes, it can be quite cold, for example on the Kluane Plateau in Yukon Territory, Canada, the coldest temperature in North America as recorded at -63°C (-81.4°F) – and that is without the windchill!

Snow is common in most areas, especially throughout winter. However, whether snow cover stays for long periods of time does depend on latitude. For example, in the alpine tundra found along the equator there may be snow, but it melts relatively quickly.

Sunlight hours in the alpine tundra

Since the alpine tundra is scattered around the earth on mountain tops, it is harder to give general hours of daylight because it depends on the latitude. Near the equator for example, night and day remain relatively equal all year, but as you go north and south you have larger differences in the amount of daylight depending on the season.

One thing that is true for all alpine tundras though is that the UV radiation is higher, because they are at such high altitudes. This means that plants need to be able to withstand stronger UV rays than those down in the temperate grassland for example.

Precipitation and wind in the alpine tundra

Similar to temperature, the amount of precipitation will change with latitude, however it also changes with altitude, or with different aspect (direction of the slope), even on the same mountain. There will normally be more rain at higher altitudes and on the windward side of the mountain (see the rainshadow effect in the desert biome).

To give an example of how varied precipitation can be in different regions: it can rain as much 64 cm (25 inches) a year in parts of The Rocky Mountains and as little as 7.6 cm (3 inches) in the northwestern Himalayas.

The wind in the alpine tundra, in any region, is harsh and cold because of the high elevation and the lack of trees. They may average 8-16 km (5-10 miles) per hour but can reach as high as 120-200 km (about 75-125 miles) per hour in the larger mountain ranges such as The Alps. Not only is the wind cold and strong, but it sometimes carries ice crystals that can actually be harmful to vegetation, especially young newly growing plants.

Soils of the alpine tundra

The soil in the alpine tundra is well drained, meaning containing little water, and thin. Similar to the arctic tundra, low plant biomass (the amount of plant material), generally low density of animals, and the low temperatures make for slow decomposition and low nutrient cycling. So plants need to be able to depend on few soil nutrients.

Since this biome occurs on mountains, there are generally plenty of large rock outcroppings, and variable terrain, with much of it being steeply sloped. This steep landscape is a big reason for thin and dry soils. The exceptions to this are flatter meadow areas and plateaus where more soil can settle and water can collect into bogs, marshes and even lakes.

In the colder more northerly climates, the soils are considered Gelisol Soils because they are dominated by freezing and thawing between seasons and there may be pockets of permafrost, though it is not as uniform as in the arctic tundra. Otherwise they are considered inceptisols, with spodosols below them. The alpine tundra that occurs on volcanoes are considered andosols because of their high ash content. In all of these soil types in this biome the soil layering and development is poor.

BIODIVERSITY IN THE ALPINE TUNDRA

What lives in the alpine tundra biome?

Since the alpine tundra can be found throughout the whole world, there are a variety of organisms that live in this biome depending on the region. Yet, plants and animals do have similar adaptations that help them to survive these difficult conditions. In the case of some animals, they have the behavioral adaptation to migrate vertically – up into the alpine tundra for the short yet productive summers, and down into forests and grasslands in the harsh winter.

Interestingly, the fact that the alpine tundra occurs above the treeline in the mountains makes them almost like little isolated “islands”. This means that there are few species in the alpine tundra, but they are usually very different between regions, because the lack of breeding with organisms from other areas results in different species. Due to this, many species are endemic, meaning that they only live in that place. In saying this, the alpine tundra is very important to world biodiversity as a whole!

Additionally, the low diversity in an area results in simple food webs and close interactions between species which are more sensitive to change because, for example, if something loses a food source it doesn’t have as many alternatives. For all these reasons, and more, it is important to protect these areas from too much disturbance.

Plant adaptations to the the alpine tundra

The cool temperatures, short growing seasons, high winds and thin dry soil mean that this biome is a difficult place for plants to grow. If you have already looked at the arctic tundra biome, you will notice a lot of the adaptations to survive in the alpine tundra are the same! There is even a large overlap in the types of plants because of the similar climate. And remember, there are no trees in the “tunturia” or “land of no trees” in Lappish.

Plants in the alpine tundra include things like: Low tussock grasses, moss and cushion plants, dwarf shrubs, lupins such as Andean Lupin or “chocho” (Lupinus mutabilis), heaths, lichens and mosses. Again, different plant communities can be found in different microclimates where grasses and slightly taller shrubs dominate areas with less wind and more developed soils, and cushion plants, lichens, and mosses take over the more difficult terrain.

You can watch this beautiful video of a variety of alpine tundra plants in Alaska:

A short growing season is one major issue to overcome. Most plants of the alpine tundra are slow growing and in general flowering plants take years before they are ready to flower and reproduce. As well, slow growth means that it can take a long time for plants here to recover from damage. However, they must take advantage of the short season and put lots of energy towards growth while they can. Plants are also mainly perennials, meaning they go dormant for winter and come back to life with spring, unlike annuals that die at the end of summer and their seeds or bulbs grow in the spring.

To get the most out of this short summer, many flowering plants blossom as soon as the snow melts, such as the blue alpine forget-me-nots (Eritrichum aretioides) which are some of the first to bloom in some North American alpine tundras.

Many plants in the alpine tundra have similar adaptations to those in the desert, such as shallow wide reaching roots and thick waxy leaves to help reduce water loss.

Plants here also have to deal with lower air pressure, meaning lower carbon dioxide and oxygen available for photosynthesis processes. Therefore, they are adapted to be able to convert light into food with less carbon dioxide than plants that live in lower elevations.

In addition to these issues, plants need to stay warm. One strategy for this is that many plants will grow very close to the ground tightly packed together to stay warmer and avoid cold air and harsh winds. A prime example being matt and cushion plants like moss campion (Silene acaulis). Other plants, such as lousewort (Pedicularis), bearberry (Arctostaphylos uva-ursi), and cottongrass (Eriophorum) also have hairy stalks which help to insult them. Just like in the arctic tundra, flowering plants have large, and often dark, flowers that absorb more heat, however, flowering plants here, such as Alpine sunflower (Rydbergia grandiflora), do not normally rotate with the sun, probably to avoid the harsh UV rays at mid day. Last, towards the end of the season, and for some plants all year, you will also notice more reddish coloring in some leaves. This coloration comes from pigments called anthocyanins which help to turn the sun’s light into heat. An example of a plant that changes colors late in the season is the alpine aven (Acomastylis rossii).

Here is a good site on plants and animals in Colorado USA’s Alpine Tundra.

Animal adaptations to the the alpine tundra

Similar to the arctic tundra, we can divide animals that live here into two groups: residents and migrants. Residents are animals that live in this area all year long, whereas migrants are animals that come into this area during summer and leave in winter. Interestingly, unlike other habitats this migration is a vertical one instead a long migration from South to North and vice versa. Alpine tundra migrants simply come up into the mountains from the valleys and forests to take advantage of rich summers, and go back down into them once the harsher weather sets in. In general, there are more migrant animals than residents. This is less prominent near the equator where there is less strong seasonality, but does still occur.

Quick note: We are trying to cover a large area in a small space with generalities for the whole biome, so we won’t be able to mention all the interesting animals that live in the alpine tundras around the world. As well, if you are researching for a project make sure you confirm which continent your animal lives on!

Animal Residents

Even though the alpine tundra occurs all over the world, a lot of the adaptations required to survive here remain the same, and are similar to adaptations for other northern habitats (arctic tundra, polar ice caps, boreal forest etc.).

Mammals and birds have round, larger builds, short ears and tails, and very thick insulating fur/feathers which all help to prevent heat loss, as well as the ability to put on fat in the short summers to help survive the long winter.

Another similar characteristic of some alpine and arctic tundra animals is the changing of their fur coats between summer and winter. White-tailed Ptarmigans (Lagopus leucura) for example not only put on thicker feathers for the winter, they also change the color from dark browns to white, and vice versa, to better help them camouflage, no matter the season.

Some animals, such as the grizzly bear (Ursus arctos), or marmots, like the yellow-bellied marmot (Marmota flaviventris), hibernate through most of the winter (up to 8 months of the year!) in order to avoid it all together. Hibernation is the act of lowering body temperature and metabolism to stay asleep for long periods of time. They have to put on a lot of weight in summer and fall, but then sleep through the most difficult season.

A famous resident of the alpine tundra is the pika (Ochotona princeps), which is a relative to the rabbit. Now, pikas don’t hibernate, instead, they hide from the weather under rocks in the boulder fields and in burrows underneath the insulating snow. Their stout bodies and short ears and tails are perfect for staying warm in winter. They work hard the entire summer collecting grasses and sedges to store in “hay piles” which they feed on throughout winter. In the spring males “sing” to attract their mates. Females can have up to 2 litters of pups a year as the young leave their mother after just 1 month. They are key species here and very important prey for animals like birds of prey, coyotes, martens, and more.

Interested in pika conservation in the USA? Go here.

An iconic apex predator of the alpine tundras of Asia is the snow leopard. This big cat is perfectly adapted to live here. With a thick winter coat, large snow shoe-like paws, and the ability to jump 3 times its body length, it can survive tough conditions and track down and hunt a variety of mammals, such as argali mountain sheep (Ovis ammon).

Though much less diverse, there are a variety of insects that also live in the tundra, such as grasshoppers, butterflies, spiders, beetles, bumblebees and more. In areas with more still water you can find species of flies but the harsh temperature definitely limits them here. Furthermore, the streams and rivers coming from glaciers have an interesting variety of aquatic macroinvertebrates. Many insects will have longer larval stages, which go dormant in winter and come alive in spring over a few years, and short adult lives where they quickly reproduce in the short summers.

Large birds of prey like golden eagles (Aquila chrysaetos) or carunculated caracara (Phalcoboenus carunculatus) soar above the alpine tundras, feeding on rodents and rabbits, though they may venture down into forests when food is scarce. Scavenger birds like condors, vultures, and ravens scour the landscape doing an important job cleaning up carcasses of dead animals. In New Zealand the curious Kea Parrot (Nestor notabilis) lives year round, both scavenging carcasses and feeding on roots and many different plants. They have thick feathers and sleep in burrows to stay warm during the cold night; they are the only parrot that lives in alpine regions.

Animal Migrants

Most ungulates, meaning hooved animals, that live in the alpine tundra carry out vertical migrations, spending warmer periods in the alpine tundra but heading down to forests and valleys before snow begins to fall. Mating season often occurs in fall in lower areas and babies are born in spring up in the rich season of the tundra, where there are a few less predators and plenty of vegetation trying to grow quickly in the short season.

Some examples of alpine tundra animal migrants are: Dall’s sheep (Ovis dalli), moose (Alces alces), chamois (Rupicapra), mountain sheep (Ovis canadensis), ibex (Capra), and North American elk (Cervus canadensis). Mountain goats (Oreamnos americanus) also migrate but spend more time at higher elevations than most.

If you have never heard an elk bugle, I think you will be surprised by the sound!

In the alpine tundra of more equatorial regions there is less seasonality, but organisms still have to be very tough to live here and there are still migrations. For example, in the South American Andes the spectacled bear (Tremarctos ornatus) lives in the alpine tundra or “Páramo” much of the year but some migrate down into montane and cloud forests seasonally to feed on abundant fruits.

Note: Fungi and microbes are also super important parts of the ecosystem, especially for helping to cycle nutrients! Scientists are learning more about them everyday but we do know that the microbial community changes a lot between seasons!

THE ALPINE TUNDRA AND US

The extreme climate, steep slopes, thin dry soils, and low air pressure makes much of the alpine tundra uninhabitable. However, we do use these regions for recreation, resource extraction, and seasonal grazing of livestock. The alpine tundra is also important to us because the water that melts off glaciers and flows down through the mountains is a major freshwater source for many populations.

The slow growth of tundra plants and the sensitive nature of simple food webs makes these habitats very fragile and means that they can take a long time to recover! So, what impact do we have on the alpine tundra?

Direct impacts on the alpine tundra by humans

Since farming is not very good here, there is little to no impact from agriculture, but there is still use of these areas for seasonal grazing. Since this migration of herd animals into these regions in summers naturally occurs with wild animals as well, it is possible to do this in a sustainable way, as long as we do not overrun the landscape with large numbers of animals and chase away native wildlife.

Resource extraction and road development are the biggest threats to the alpine tundra. If areas are dug up it can take decades to recover the vegetation naturally. New roadways can decimate important stretches of habitat containing rare plants.

Tourism is also very important in these regions, from hiking in summer to skiing in winter, these alpine regions are truly spectacular to visit. Recreation can have a minor impact if done properly but development and overuse is very harmful to these sensitive places. Trampling of plants, even just by walking, can cause serious damage to an area, and trash left behind can cause pollution or even cover up some sensitive plants from the little available light, killing them.

Indirect human impacts on the alpine tundra

The biggest indirect threat to the alpine tundra is climate change. The shift in climate is causing these habitats to shrink because the treeline is moving higher in many regions. As well, areas that are already dry are experiencing even drier climates and faster snow melt. Glaciers worldwide are shrinking more every year instead of growing in the winter, causing less water to melt off in the spring. This melt off is an important water source to feed streams and rivers that are crucial to biomes below.

Research conducted in Europe shows that as little as a 1.5°C change in temperature could result in about 30-70% of loss of European alpine tundra habitats in different mountain ranges!

What we are doing to mitigate these issues and what can you do?

The harsh environment which makes it difficult for human settlement has helped save much of this area from development. Many national and provincial parks are established in alpine tundras, with recreation allowed so that we can enjoy these beautiful areas but still protect these unique pockets of rare diversity.

One thing you can do to protect the alpine tundra is to use parks responsibly. If you go into these areas it is key to keep yourself, your vehicle and even pets on the trail and on rocks so you don’t trample sensitive plants. Also, follow the code of “leave no trace” which means packing out all your garbage and waste and not altering any habitat, including stacking rocks or taking plants home with you. This can damage precious habitats!

For mining and road development, it is important for companies and governments to carry out research and find the best areas to extract or pave to help disturb as little wildlife and plants as possible, as well as implementing environmental rehabilitation after the works are complete.

Climate change can seem very overwhelming to combat, but making personal environmentally friendly choices does make a difference. Reducing how much you use the car, buying less things to help lower production, buying from more sustainable companies, and eating less meat are some small things you can do to help. As well, joining environmental clubs and lobbying your government and big companies to make greener choices goes a long way!

Interested in research? GLORIA is a worldwide organization dedicated to studying alpine habitats.

The alpine tundra biome is an incredibly diverse and sensitive place that is home to a variety of weird and wonderful animals, and that is enjoyed by many people as well! We have to treasure these places and do what we can to protect them, because even if they may seem harsh and barren at first glance, they are important contributors to biodiversity, and like any natural place, deserve our respect and care.

Images from the Alpine Tundra on the Equator

The following images are from the Páramo in Ecuador, which is close to the equator. Below this alpine tundra is lush tropical rainforests.

Ready to explore this in Virtual Reality

The following video is of Elbrus Mountain in Russia. Try to note when you’re above treeline (and hence, in the alpine tundra). Take note of the plants that inhabit this zone.